Forthcoming legislation (including the new EU MDR regulations that come into force in May 2020) also require labelling content to be published electronically. As companies seek to continuously differentiate themselves in established markets as well as enter new territories, the increase in both volume and complexity of product and market variations will have a direct impact on labelling.

Many of the processes that organisations currently have in place try to manage this problem using documented systems and procedures. These typically define a series of steps to be followed and information to be captured, along with what to do if certain criteria either exist or don’t.

Guidelines and instructions are usually captured in procedural manuals and can quickly become out of date or uncontrolled if not managed carefully. This can be compounded by some taking on the role of the “go-to person” for direction and advice; all too quickly, the organisation finds itself operating on the basis of “tribal knowledge.”

Historical overview

Some early attempts to address these challenges can be seen in the approaches taken by labelling software vendors offering solutions for downstream print and packaging (typically shipper case and carton labelling). These solutions often rely on fairly low-level integration with product lifecycle management (PLM) platforms, applying simple rule criteria to generate the correct output.

Although this type of approach can be effective in satisfying labelling requirements at the point where products are packed for shipping, it fails to address the upstream challenges at the point of primary and secondary packaging. It also omits the need to publish product related information electronically.

Quite often, these types of software solutions, despite being cloud-based, are effectively “local software instances,” meaning that each production facility would have its own set of rules and predetermined user interface (UI).

This can restrict choices when, for example, wishing to engage new partners and can increase production costs and other overheads as the business scales. It can also make it difficult to share and trace the use of content across the enterprise, making it harder to prove compliance and maintain alignment with corporate standards.

As outlined above, many of the overheads and risks to non-compliance associated with label print and production are the cause of three main factors:

- reliance on tribal knowledge or a go-to person for the explanation or interpretation of requirements

- little of this knowledge and labelling content is captured electronically, creating an increased risk of non-compliance the more decentralised an organisation becomes

- legacy stovepipe applications with minimal process integration that can obfuscate key elements of data and restrict the flow of information.

With one or more of the above factors present, any organisation seeking to increase its global reach and product portfolio is likely to experience levels of disruption. This could lead to production downtime or product recalls, ultimately impacting profitability and market reputation.

A survey of 285 senior executives done by Ernst & Young on the effectiveness of decision making within the consumer sector suggested that employees spent too much time making decisions based on intuition, working on mechanical tasks and focusing on unnecessary detail. A recent study by Forbes also revealed that 98% of managers fail to apply best practices when making decisions.

Focusing back on the life sciences industry and with e-labelling and more patient-centric treatments around the corner, it is likely that organisations will begin to experience an exponential growth in the volume of variable content that needs to be shared with both the prescriber and the patient.

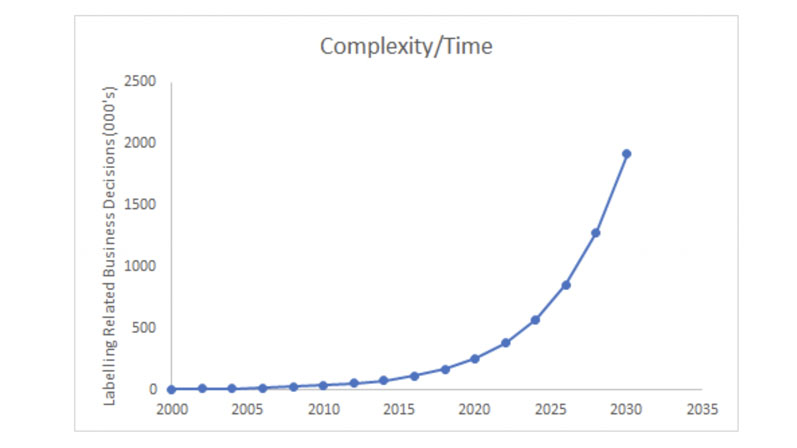

This, in turn, will impact on the number of business decisions that will need to be made when it comes to labelling. Loosely based on Moore’s Law, Figure 1 gives a projection of how the number of decisions related to labelling content is likely to increase with time. This suggests that without some form of decision support system, labelling teams will not be able to respond effectively to increased levels of sophistication and complexity.

Figure 1: The number of decisions related to labelling content will increase with time

The combination of a broadening product portfolio, expanding market presence and increasing legislative requirements has already seen the number of decisions needed to ensure appropriate and accurate labelling content increase with time. This trend will continue as recent regulations and directives impacting labelling requirements within the medical device, pharmaceutical, chemical and cosmetic industries begin to mature.

Adopting a manual-based approach is sustainable to a point, but risks labelling and artwork content falling out of compliance with corporate standards and local regulations. In effect, there is little corporate governance. There are rules, of course, but the accurate execution of these rules relies on human awareness and precise interpretation.

Consequently, those responsible for collating and entering labelling content waste time searching for the correct information and instructions buried within emails, PDF files and databases.

As a result, in-country affiliates can become overburdened with an unnecessary level of complexity. New staff and supply chain partners responsible for print and packaging need to manually learn each of the rules associated with label creation, which can impact both timeliness and value.

This can lead to frustration, fatigue and, in some cases, discrepancies and uncontrolled variations. Furthermore, it becomes almost impossible to identify the source of errors as instructions and guidance notes are often uncontrolled, untraceable and out of date.

A business rules approach

Some might argue that more processes and greater levels of documentation are required to solve this problem, but there is no guarantee that such an approach will increase levels of accuracy and quality.

A much better approach is to harness both corporate knowledge and labelling content and embed these into the software tools used by those across all functions of the supply chain — from regulatory right through to final packaging and shipment. This suggests a need for a labelling and artwork-centric business rules engine to achieve each of the desired outcomes given below:

- minimise the level of human intervention required to complete complex tasks

- ensure content alignment across all types of labelling

- automate and simplify the capture and collation of labelling content needed to address specific product and market needs.

At its simplest level, a rules engine consists of a set of instructions that can act upon a number of “facts” stored within a “fact model.” The accuracy and quality of any decision being determined by the data and facts stored within the application.

In the context of labelling, a fact may be a statement, symbol, image, phrase, barcode or any other component appearing on a label. The rules engine itself requires that it is prepopulated with a set of facts to which rules can be applied to derive more facts. Once configured, the rules can be executed as part of the core business application.

Why deploy a rules engine?

Business rules engines (BRE) and business rules management systems (BRMS) are acknowledged as being the most effective approaches to developing these kinds of decision making systems. Managing the decision making logic as a set of business rules allows for more responsive changes or additions to logic as this can be undertaken by business users as opposed to writing code.

This approach also simplifies the ongoing management of decision making logic and also allows for new business logic to be modelled without impacting the existing underlying processes.

Moving business logic that is either hard coded in software systems or exists as a set of instructions contained in documents and emails into a business rules engine also simplifies ongoing management and change.

Mark Allen of Progress Corticon suggests that having the business rules logic separated out from the underlying application can help to make business logic 10–25 times faster by removing the backlog of requested changes placed on IT. Allen also states that a BRMS can significantly reduce the need for manual processing as well as help to ensure compliance with regulations and suggests the following benefits are likely to be realised:

- being better positioned to keep up with the pace of change

- improvements to productivity and efficiency

- ensure compliance with policy and regulation

- improve customer service

- open new revenue opportunities.

Software systems that have automated what were operational and repetitive decisions have shown to improve organisational decision making and corporate knowledge. Instead of being written down in documents and or emails, these elements are continuously enriched and enhanced by new insights.

Given the complexities of the labelling environment, we now need to consider whether taking a business rule driven approach to labelling and artwork has the potential to deliver real benefits.