ChristianaCare’s Cawley Center for Translational Cancer Research has unveiled a first-of-its-kind organoid core in a community cancer centre programme.

The new laboratory facility within the Helen F. Graham Cancer Center & Research Institute grows and tests living, patient-derived tumour models, giving doctors and researchers a faster, more precise way to identify the therapies most likely to work for each patient.

This innovation could change how cancer is treated in Delaware and serve as a model for community centres nationwide.

There are only a handful of organoid core centres, or “tumour-on-a-chip” programmes, in the US and ChristianaCare’s is the first within a community cancer centre setting.

What the organoid core does

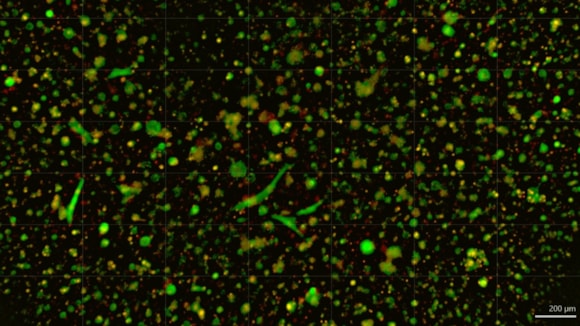

Tumour organoids are tiny, three-dimensional cultures grown from a patient’s tumour tissue.

They preserve the genetic and molecular traits of the original tumour, making them far more accurate than traditional cell lines.

“These mini-tumours enable researchers to screen drugs faster, identify new biomarkers and discover which treatments are most likely to work for each patient,” said Dr Thomas Schwaab, Bank of America Endowed Medical Director of ChristianaCare’s Helen F. Graham Cancer Center and Research Institute.

"This core is a bridge between the lab and the clinic."

"By growing living tumour models from cells of individual patients, we can test real-world drug responses and tailor treatments for them in ways that were not possible before.”

How does it advance patient care?

The organoid core strengthens the Cawley Center's research capabilities by enabling drug screening and biomarker discovery.

It will bank organoids representing the wide variety of tumours seen in the community, giving scientists a realistic system for testing therapies.

It will bank organoids representing the wide variety of tumours seen in the community, giving scientists a realistic system for testing therapies.

ChristianaCare treats more than 70 per cent of cancer patients in Delaware, giving researchers unique access to treatment-naïve samples.

These are tumour tissues that have not yet been exposed to chemotherapy or other therapies.

Studying them provides a more accurate picture of how cancer behaves naturally and how it might respond to new treatments.

Bringing a new cancer drug to patients is expensive and risky.

Estimates show it can cost $1.3 to $2.8bn, with up to a third spent on preclinical development and only about one in ten compounds ever reach human trials.

Traditional mouse models often fail to fully mimic human tumours, making early testing less reliable.

By using organoid screening, the Cawley Center can test therapies more accurately, reduce costs and failure rates and move promising treatments into clinical trials faster.

Combined with existing tissue collection programmes, clinical trial infrastructure and community partnerships, these resources create a direct pathway to bring lab discoveries to patients faster.

Turning point in translational research

“Our goal is to shorten the distance between discovery and treatment,” said Dr Nicholas J. Petrelli, Director of the Cawley Center.

"Too many promising drugs fail as early models do not capture the complexity of real tumours."

"The organoid core helps solve that problem. We can now test therapies in models that reflect the patients we actually serve.”

“This is a turning point for translational research in community health,” said Dr Jennifer Sims Mourtada, Associate Director at the Cawley Center.

“Organoid technology lets us study cancer in a way that feels personal."

"We are not just looking at data points. We are studying living models of a patient’s tumour, which can reveal how that person’s cancer might behave or respond to treatment."

"This approach brings science closer to the people it is meant to help.”

Looking ahead

In the coming months, the organoid core will focus on building a diverse biobank of tumours common in Delaware.

Plans include collaborations with academic institutions, shared access for external researchers and development of immune-tumour co-culture models.

By combining advanced technology, strong community partnerships and direct patient access, ChristianaCare and the Cawley Center are showing how translational cancer research can thrive in a community setting, making breakthroughs not only in the lab but also in patients’ lives.