You would have found it hard to write a retrospective on the clean air and containment sector 50 years ago. This is because it didn’t exist. There were devices that limited toxic fumes and kept the environment clear, but there was no regulated industry to speak of as such. This started to change, gradually, and gave companies such as Envair a reason to exist.

The changes we have experienced mirror those in the wider industry. We have seen the steady introduction of standards for products manufactured in labs to protect both operators and the end user, the development of pioneering technologies that have helped to validate processes and, finally, the integration of third-party solutions that are enhancing production methods and creating new levels of efficiency.

Setting new standards

Our company was born in North West England and shaped by the heavy industries that were present in the region at the time. We started out by making horizontal and vertical laminar flow cabinets as they were then called, constructed from MDF and incorporating fans and HEPA filters.

We were led by Managing Director, Peter Starkey, who had previously been a salesman for a company that sold these filters (which had been developed from ones that protected miners from coal dust).

The founders were motivated by a desire to use their engineering skills in environmental control … and that value has been present throughout the company’s history. We had only been in existence for a short time when we found ourselves building cleanrooms for companies who were at the forefront of their respective fields.

Among them were glass manufacturer, Pilkington, who needed cleanrooms for the production of head-up displays in fighter jets and for the extrusion of fibre optic cables; British Aerospace, who needed them for the production and maintenance of instrumentation; and electrical engineering firm, Ferranti, who needed them for the manufacture of semiconductor devices.

Further afield were diamond company, De Beers, in Ireland, who wanted to avoid contamination while grading industrial diamond powders and the Government Veterinary Service in Iceland who needed to be self-sufficient when it came to processing animal vaccines.

In the late 1970s, demand for cleanroom technology was growing, as was our client list. At the same time, the company was called into action by a singular tragedy. In 1978, a medical photographer called Janet Parker died of smallpox. The virus was thought to have been contracted from a poorly maintained service duct running between her workplace and a research laboratory.

This incident led to the creation of British Standard BS 5726:1979 for microbiological safety cabinets and resulted in our company entering a new area with its first range of microbiological safety cabinets. Indeed, we went on to play a leading role in that sector, with John Neiger, one of our founders, joining the British Standards committee for microbiological safety cabinets.

The next step forward came when senior pharmacists at two major hospitals, the Royal Liverpool and Sheffield Hallamshire, worked with us to develop and test prototypes of what quickly became our two main isolator ranges: Pharm-Assist positive pressure isolators for TPNs and IVs, and CDC negative pressure isolators for cytotoxics.

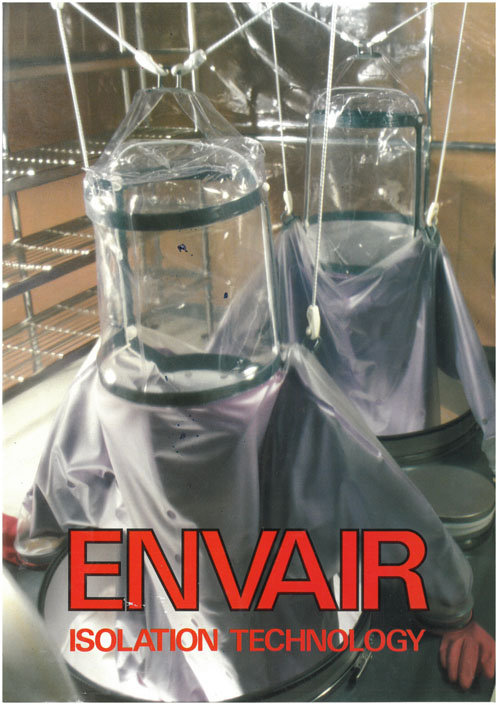

Isolators are effectively sealed enclosures with filtered airflow systems, with operator access via glove-sleeve systems and material ingress and egress via transfer chambers or transfer devices.

Again, Envair was at the forefront of developing best practice, with John Neiger bringing Envair’s expertise to the UK Pharmaceutical Isolator Working Group. The various standards and guidelines developed at this time did a huge amount to change working practices in the industry.

For example, whereas engineers had previously done pressure decay testing for isolator leaks every 6 months or so, the guidelines turned this into a routine weekly duty for operators with the test built into the instrumentation of the isolator itself, thus also facilitating validation.

Using new technology

This need to validate processes in a repeatable way and reduce the potential for human error has been a huge driver behind the development of the new technology. This includes solutions that now seem simple by today’s standards, such as interlocking doors.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that the risk of operators leaving two doors of an isolator open at once — creating an obvious risk of contamination — was recognised. Envair solved this problem by using interlocked and timed electromagnetic doors that proved to be a more reliable solution than alternative methods in use at the time.

Other developments to help operators have included the introduction of touchscreen displays inside the cabinets. Again, this now sems like a simple innovation, but it has transformed the experience of using isolators and marked a sea change from the cumbersome combination of buttons, dials and gauges that preceded it. In the words of one pharmaceutical employee: “This is like going from a Nokia 3310 to an iPhone.”

The big benefit this had for operators was comfort. They no longer had to contort themselves to read instructions on the outside of the isolator while having their hands buried in gloves inside — which also had implications for the integrity of the drugs they were working on. An operator who is both comfortable and in control is much less likely to make mistakes.

Integrating new solutions

Beyond the technology in the cabinets themselves, we are also seeing the introduction and integration of complementary equipment and computing. This includes the rapid gassing of items going inside isolators. This technology uses vaporised hydrogen peroxide (VHP) to deliver a 6-log reduction in pathogens. When it comes to validating processes in a repeatable way, this is far more effective than the “spray and pray” technique, which is still used in many labs.

Both the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and Annex 1 of the EU GMP advocate the adoption of this technology.

It can also achieve decontamination within 30 minutes, as opposed to conventional gassing techniques that tend to be done overnight. With there now being an expectation that cancer drugs be delivered to newly diagnosed patients within 4 hours, this is a revolutionary development.

A determination to provide the best care given to cancer patients has also seen the integration of software solutions, such BD Cato, which is helping operators to produce precise dosages of critical drugs. This extra tool provides relevant diagnostic data and can even guide an operator through the production process.

Looking ahead

Few can have imagined software guiding operators through the preparation of complex, cytotoxic chemicals 50 years ago, but technology evolves rapidly. As we look to find new ways to develop solutions that reduce the potential for errors, expect the innovations to continue.

For instance, one emerging area of technology in which we expect to see growth is in the adoption of robotics — perhaps the ultimate way to validate and replicate precise tasks. We could well see robots making compounds and filling syringes and chemotherapy bags in the not-too-distant future.

Whatever changes we see, the clean air and containment industry needs to stay true to its founding principles. Innovation is helpful to us insofar as it protects everyone, including operators and the end user of the product being manufactured.

It’s estimated that drug errors classified as “definitely avoidable” were responsible for approximately 700 deaths in the NHS last year. Although the financial cost of these incidents is around £98.5 million per annum, the untold heartache to families and friends is incalculable.

Reducing that total is a pressing issue for all of us. And it’s one of the reasons why the demand for containment solutions is growing. We’ve also seen COVID and the increase in cancer detection rates driving greater need for aseptic services. In the last few years, however, labs and hospital pharmacies have struggled to procure lifesaving clean air technology at the rate they would have wished.

This is why Envair recently became an accredited supplier on the HealthTrust Europe framework, which helps healthcare providers to make faster and more informed purchasing decisions. During the next 50 years, the world needs us to be every bit as innovative and as meticulous as we were in the last half century.

We’ve come a long way in that time, but the need for better clean air solutions remains … and there is still work to do.