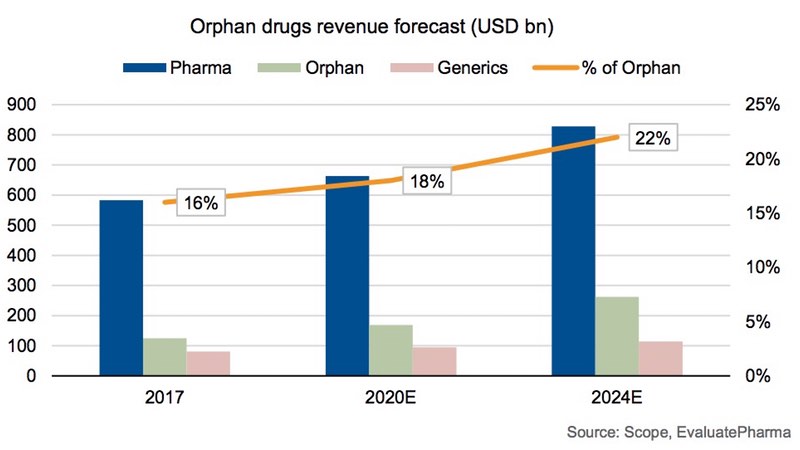

Sales of treatments for rare diseases—known as orphan drugs—are growing fast. According to German ratings agency Scope, revenue will grow by around 12% a year between 2019 and 2024, outpacing the industry's otherwise robust overall growth. Orphan drugs will account for an estimated 22% of this overall pharmaceutical revenue in 2024, more than double the contribution from generic drugs.

Big pharma is facing down critics worried that expiring patents, a lack of new blockbuster treatments, constrained public healthcare budgets and squeezed drug prices would up-end its business model. The success of orphan drugs is one reason why.

"Developing orphan drugs is a high-cost, low-volume business," says Olaf Tölke, Head of Corporate Research at Scope. "But with that comes some advantages for deep-pocketed pharmaceutical companies: barriers to entry are high for smaller competitors; and profit margins are healthy given that there are a large number of rare diseases and strong demand from health authorities, doctors and patients for effective treatments," he adds.

Bringing a new orphan drug to market costs as much as five times more than run-of-the-mill drugs, Tölke explains, which is why "pharmaceutical companies have been able to justify prices running into hundreds of thousands of dollars per patient or more".

Orphan drugs revenue forecast (USD bn)

Switzerland's Novartis makes Zolgensma, a US$2 million gene therapy so far approved for small children suffering from spinal muscular atrophy, a rare but fatal muscle-wasting disease. The company has recorded revenue of $175m since the drug's launch early this year.

Around 7,000 rare diseases affect an estimated 350 million people worldwide, according to Global Genes, but there might be only a few hundred or thousand sufferers in any one country, with, until recently, few treatment options. The US FDA now gives special "orphan drug" status to potential treatments for rare diseases, changing the approach of regulators and pharmaceutical companies and leading to growing investment in the sector.

The shift is proving lucrative for the healthcare sector. "Profit margins for the world's biggest pharma companies have proved resilient in recent years despite concerns about top-selling drugs losing patent protection, falling prices and rising costs, among other issues," says Tölke. Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation at the biggest drugmakers by revenue - Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and Sanofi – held steady at 25% to 40% of revenue between 2014 and 2018.

"Helped by orphan drug sales, the big pharmaceutical firms can be confident of similar stability in the years ahead despite a gloomier global economic context," he concludes.