Credit where credit’s due. Not only did the Lithuanian biotechnology and life sciences industry show resilience in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, it actually expanded and grew. According to State Tax Inspectorate reports, some €300 million shored up the budget during the first half of 2021.

Although assigned to the 100 largest corporate tax payers, it’s interesting to note that Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics was among the largest contributors (more than €100 million). Economy analysts predict that the company’s reagent exports alone could raise Lithuania’s gross domestic product (GDP) by at least 1% and, with Thermo’s activities ranging from PCR testing products and viral spike materials for Big Pharma, it looks like there’s more to come.

According to a recent press release and information from Enterprise Lithuania, there are currently more than 550 companies working in the greater life sciences sector in the country. Boasting in excess of 15,000 researchers, and with scientists conducting 650-plus clinical trials in 2021, it’s possible that Vilnius University’s Professor Virginijus Šikšnys has played a significant role in attracting so much attention to this nation of just 2.8 million people.

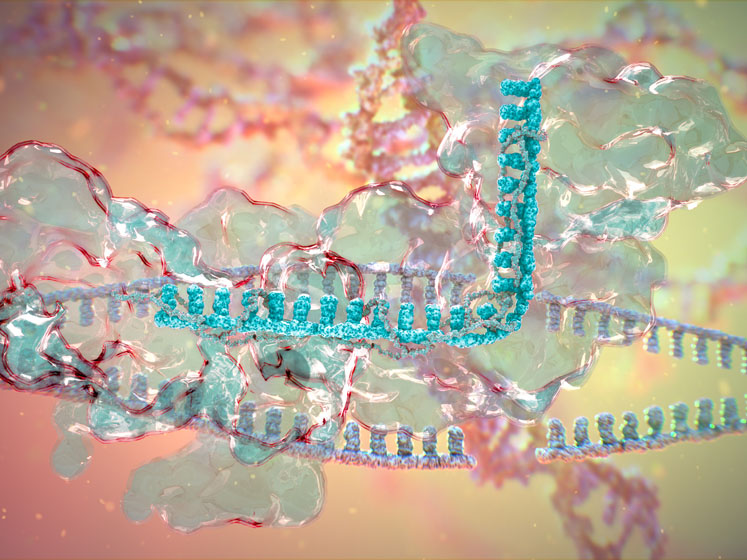

For the discovery of so-called genetic scissors, he was awarded Harvard University’s prestigious Warren Alpert Prize and, together with the 2020 Nobel laureates in Chemistry, the famed Kavli Prize for the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing nanotool.

Aušrinė Armonaitė

Shining such a powerful global spotlight on one of biotechnology’s most promising subsectors — cell and gene therapies — it’s perhaps no surprise that many local enterprises have strong ties to the Vilnius University Life Sciences Centre. Three bioscience institutes at Vilnius University, together with the Centre for Innovative Medicine, form a hub for CGT research in the area.

It’s also home to domestic local start-ups including CasZyme (the company established and led by Prof. Šikšnys), Droplet Genomics and Froceth, which develops frozen cell therapy solutions for cancer immunotherapy, tissue regeneration and the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

Furthermore, Invest Lithuania believes that the native life sciences sector in Lithuania is regarded as one of the most highly developed in Central and Eastern Europe. With a robust ecosystem of up-and-coming start-ups, the sector is driven significantly by innovation and aims to become Europe’s next major hub. International investors benefit from the presence of top-tier scientists, a business-friendly environment, exceptional governmental support and a litany of financial incentives that enable companies to ramp up quickly.

For instance, Thermo Fisher Scientific came to Lithuania in 2010 when the company acquired a leading local biotech company, Fermentas, for $260 million. Now, Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics, UAB, employs more than 1760 people in a variety of roles — including 100 researchers — making it one of the largest private R&D centres in the region.

The company’s contribution to the state budget was €54 million in 2020, compared with €30.8 million in 2019, and, according to the company, “the availability of qualified professionals in the market [has] enabled them to expand the Vilnius branch and thus ensure greater efficiency in serving customers all over the world.”

Having created more than 630 new jobs since the beginning of 2020, built a new production facility and set new heights in terms of average salaries, Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics is certainly the poster child of what government sources describe as a “thriving and inviting ecosystem that helps foreign companies to discover the opportunities that await them in Lithuania.”

CRISPR technology

But, says Armonaitė, the Lithuanian biotech sector is “not just Thermo and not just academics such as Professor Šikšnys. We have an incredible mixture of knowledge, talent and business acumen.” In fact, with biotechnology and the life sciences gaining firmer ground in the country, the government has set a goal to increase its GDP share to 5% by 2030, thereby placing Lithuania alongside Singapore, which is one of the global leaders in the field.

“Lithuania values its potential in the field of life sciences,” she adds, “and has therefore set a strategic goal of becoming Europe’s most attractive country in the sector by 2030.” This is ambitious, she concedes, but €678.9 million from EU funds has already been allocated to promote research and development, whereas a further €400 million has been invested to advance the required industry infrastructure. “Moreover, the environment in which to grow biotechnology start-ups is developing swiftly,” she comments.

“There is work to do, though,” she explains: “We need to strengthen the existing relationships between academia and the country’s business ecosystem, further develop the technology transfer infrastructure and forge stronger links between bench research and industry. Our aim is to create a safe environment of trust for cutting-edge science.”

“Many young companies suffer from a lack of investment,” notes Armonaitė, “but we’re addressing that with a number of financial initiatives. At the same time, we recognise that we’re a comparatively small market, so it’s important not to be naïve.”

As such, there’s currently a stronger focus on creating a robust business-to-business environment as opposed to a business-to-consumer market. “Along with the European Commission strategy to attract financial support, we’re working to increase our domestic capacities in various sectors — including information and communications technology (ICT), high-tech engineering and, of course biotechnology — to make the European Union (EU) more independent and less reliant on super economies such as the US and China for products such as personal protection equipment.”

“Lithuania is very much an open and export-based economy,” notes the Minister, which she describes as “an opportunity. Globalisation is not a threat; it’s something that makes us stronger and more significant.”

Given that the country’s GDP actually grew during lockdown, and the national focus on a circular bioeconomy, it’s easy to understand why the onus is on putting future plans in place to establish a resilient funding model that stipulates reform as opposed to recovery. “With more than 8000 manufacturing companies in Lithuania, we need to focus on sustainability, the environment and increasing our national output,” she adds.

In 2019, Lithuania had an export intensity index of 87%, a 47% share of which remained within the EU and, between 2015 and 2020, the average annual growth rate of exports was 22.3% with a value of €627 million (in 2020). Among the most popular items that made border crossings were medical instruments, enzymes, nucleic acids and their salts, antisera, immunological products and acyclic hydrocarbons. Very much a one-way street.

People, people, people

Despite the rapid progress being made in fields such as artificial intelligence and robotics, no business (yet) can function effectively without living and breathing employees. Here, Lithuania scores again. The country is populated with a young, highly qualified talent pool: 53% of Lithuanians are fluent in at least two foreign languages and 56% have enrolled in higher education programmes (impressively, as well, 57% of Lithuania’s scientists and engineers are women).

The ebb and flow of the “talent pool” varies widely according to who you talk to, but Armonaitė reminds me that “Lithuania is a country of emigration. There was a huge diaspora to the US, UK and Australia in the past, but we’re now promoting very positive messages to reverse this historical brain drain and attract people back.”

At the same time, the country has embraced an open border policy for everyone. In what Armonaitė describes as a “liberal immigration” programme, companies considering foreign direct investment in Lithuania may qualify for state funding, which is negotiated on a case-by-case basis in compliance with EU and national legislation.

There’s also a reduced labour tax for new arrivals and subsidies or compensation for organisations that attract foreign talent. Furthermore, to promote entrepreneurialism, Lithuania’s government offers companies the opportunity to reduce their research and development expenses; in fact, they’re fully tax-deductible three times during the tax period in which they’re incurred.

Finally, as well as offering seven Free Economic Zones in various locations across the country, all offering ready-to-build industrial sites with physical and/or legal infrastructure support and services, the Lithuanian parliament has now adopted a new package of laws (as of 1 January 2021) that provides significant tax incentives for large-scale projects. These include 0% corporate tax for 20 years (based on an initial investment of at least €20 million), as well as streamlining the key processes involved in land acquisition, planning and migration.

In conclusion

From an outsider’s point of view, though, not all is rosy in the garden: most of the large foreign companies that have established themselves in Lithuania did so on a merger and acquisition basis. They bought out smaller local entities as opposed to making greenfield investments. So, now, the biggest players in the country are headquartered overseas.

Enterprise Lithuania advocates a stronger focus on venture capitalism — as long as all the security boxes have been ticked — to increase the level of angel investment in domestic start-ups and reduce the currently long lead development times for new products.

Of note, that type of financial support has increased from €1 to €8 million in recent years, so the message is certainly spreading; but, there are calls for a greater knowledge base in terms of risk management, commercialisation and long-term business strategies.

And whereas Brexit may offer benefits in terms of advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) regulation, questions are being raised about the export versus internal use balance. Ironically, perhaps, an unfortunate side-effect of successfully communicating the advantages of breakthroughs such as CRISPR to a well-educated and accepting society.

On a very cold winter morning in the stunning capital city of Vilnius, it’s encouraging to hear that warm air is being blown into Lithuania’s burgeoning biotechnology bubble. One can only hope, however, that the membrane of that bubble is not only flexible, robust and capacious, it’s also semi-permeable.