Essentially, the pandemic has shown the strengths and weaknesses of the global healthcare sector — and the opportunities that exist for improvement and transformation. While demonstrating what can be achieved through global collaboration, COVID-19 has also shone a harsh light on the disparities in healthcare access between developed and developing countries.

The lack of access to innovative medicines goes far beyond vaccines, for example, to biologics such as insulin. Although the discovery of insulin was made 100 years ago, access to this drug for the treatment of diabetes is still limited in many parts of the world— often where the disease is now becoming most prevalent.

At the same time, governments across the world, including low- and middle-income countries, are increasingly held responsible for their populations’ health and access to relevant medicines. This pressure has been further increased by the pandemic and its focus on the performance of different healthcare systems.

These needs are driving a requirement to expand capabilities around innovation and access in low- and middle-income countries, which will have a potentially transformative impact on the wider global healthcare ecosystem, including pharmaceutical companies, governments and other stakeholders. The wider industry should therefore look to understand and answer these five key questions.

- How can low- to middle-income countries improve access to innovative medicines for their citizens?

- What capabilities are required to rebalance the current supply chain and bring production to these countries?

- How would the increasingly local production of vaccines and biologics change the global supply chain?

- Are there faster and easier ways to develop, produce and distribute not only vaccines, but also other innovative drugs, in and for developing markets?

- What new and innovative approaches are already in place, and how will this change the market, in both the developing and developed world?

The pandemic has highlighted what the global life sciences industry can achieve in a remarkably short time, with the development of a multitude of novel (and successful) vaccine approaches that were quickly rolled out around the globe.

Moving beyond COVID-19, bringing innovative medicines to developing markets — and using the lessons learned to improve healthcare outcomes in the rest of the world — must focus on two key areas for innovation – access and manufacturing – while also considering R&D and enabling a different kind of innovation.

Increasing access for wider populations

Access to medication, whether produced locally or internationally, is a key challenge that’s based on factors such as cost, availability, healthcare systems, reimbursement models and the potential difficulties of physical distribution, especially when this involves cold-chain logistics and delivery in sparsely populated areas.

The required ecosystem thinking to establish clinical trials in these regions has recently been demonstrated through the first malaria vaccine, which was approved and recommended by the WHO.

However, this access challenge is also driving a very different innovation; for example, Zipline, a US-based drone company, recently completed the first long-range drone delivery of authorised mRNA COVID-19 vaccines requiring an ultra-cold chain in Ghana.

The collaboration will allow the distribution of approximately 50,000 doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in the country, pioneering a new distribution model that overcomes the twin issues of limited infrastructure and widely spread populations. This approach could ultimately be rolled out in Europe, Asia-Pacific and the Americas, especially in areas with a low population density.

Availability, particularly of vaccines, has become a key consideration for national security, with the allied consideration of using healthcare as a tool to manage foreign policy. The former relates to ensuring that key medicines are available on call for all … and the latter to the possibility of substituting capital with healthcare.

Bridging the production gap by thinking locally and globally

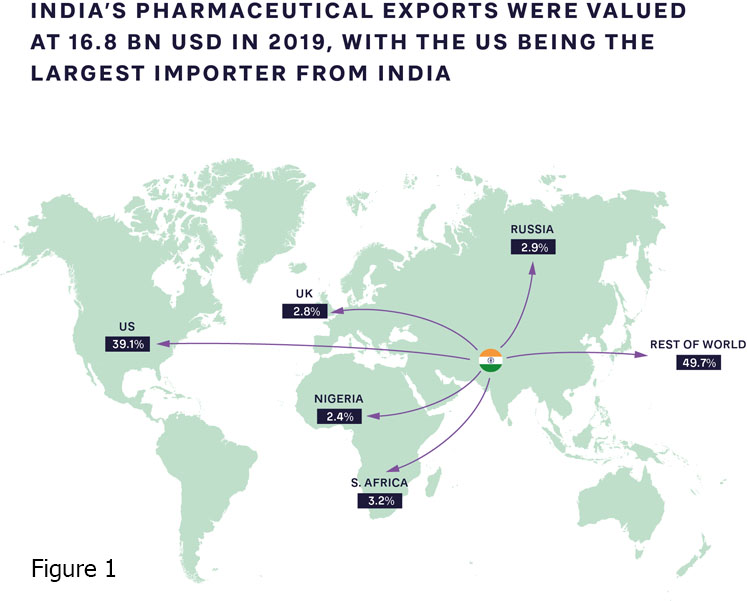

The pandemic has accelerated the push for local, high-quality production of patented medications, supported by their originators, alongside open business and operating models that include partnerships with international organisations. Production capabilities and ecosystems clearly vary widely; India is increasingly becoming the “pharmacy of the world,” introducing innovative new approaches (Figure 1).

Meanwhile, there are fewer than 10 vaccine manufacturers in Africa, most of which are in Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal and South Africa. Steps are being taken to expand this capacity.

Some countries in South-East Asia have long realised that their healthcare systems are being put under significant stress by

- high pharmaceutical spending owing to a preference for imported patented drugs and branded generic drugs

- reliance on imported active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) — making up 90% of local API consumption — and drugs (64% of local drug consumption) owing to the lack of local development and manufacturing capabilities and capacity

- a lack of a pharmaceutical ecosystem in the region, with gaps in the value chain, specifically in research and development.

These factors are exacerbated by the changing dynamics of a market that is rapidly expanding economically, driving significant growth and change in the population. This has led to various chronic health issues that are now aggravated by the uncertainty caused by the current pandemic.

Although there is currently an intense discussion about releasing patents for vaccines, it is important to look at the broader question of what it will take to enable the local production and supply of innovative medicines. Beyond IP, countries looking to build local production (and local R&D) need to develop multiple capabilities alongside the investment and time required to build production facilities, including

- universities with the freedom and resources to do research

- trained people who are able to master complex production technologies

- infrastructure that ensures a steady and uninterrupted supply of water and energy to run production facilities

- sterile production processes with extremely high-quality standards and, in many cases, a cold chain

- legal and regulatory frameworks to ensure that quality and liability are covered adequately.

The opportunity for innovative manufacturing and R&D approaches to improve access for all

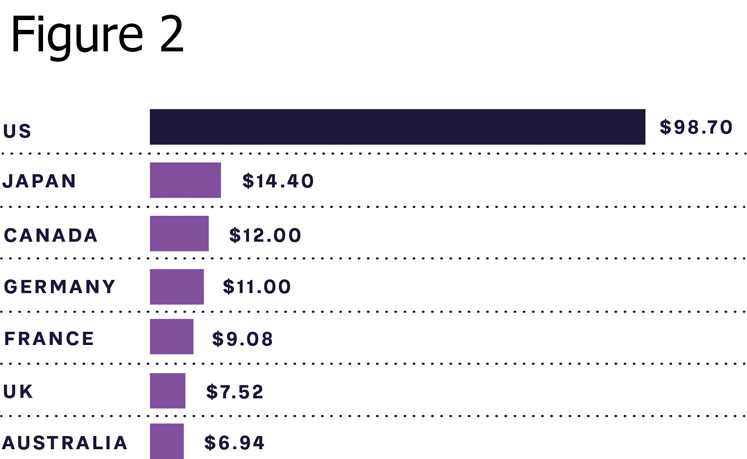

As can be seen from Figure 2, the cost of insulin, which is a necessity for type 1 diabetes (T1D) patients to survive and highly relevant for many type 2 diabetes patients to control blood sugar levels and avoid long-term side effects, is still high in many markets. This includes the US, which has out-of-pocket treatment costs close to $1000 a month for T1D patients.

Indian company Biocon has created its “10 cents” initiative for insulin, bringing the price down from about $5 to just 10 cents per day for treatment in India. As part of this initiative, Biocon is the first company to develop and market insulin produced by the Pichia pastoris yeast, which allows for faster and more efficient production compared with current methods.

Innovation is not limited to insulin; our recent study on biologics production shows that new methods have a much higher chance of adoption in countries such as India. These less “settled” markets are proving to be more open to innovation as they are often still building new production systems and less bound by existing facilities and preconceptions in the market.

Additionally, the fear of using a new system that might not yet have regulatory approval is much lower, meaning companies are more likely to take risks. Once proven, these approaches can then be applied within developed countries, bringing benefits in terms of decreased manufacturing costs and lower supply chain risk.

The benefits and opportunities of rebalancing for all players

Transforming access to innovative medicines requires a joined-up approach that shares best practice and develops new capabilities in low- and middle-income countries. As the experiences of India, China and other countries demonstrate, this rebalancing is already happening and likely to accelerate post-pandemic.

Given these trends, should established global life science companies, policy makers and governments fear this global shift led by low-cost production and innovation and new access methods across the developing world?

The answer is a resounding no. In addition to considering risk, all players should look at the value and opportunities provided to global and local healthcare by initiatives targeting, for example, the reuse of existing drugs, innovative approaches to generics and biosimilars, and even innovative distribution models such as drone delivery.

Different regions bring value to different parts of the healthcare system; supporting local production and innovation for more patient-centric — but also cheaper and more accessible — medications will ultimately be a global benefit. Lessons can be learned and innovative approaches adopted that can be applied within the developed world.

Authors: Dr Franziska Thomas, Partner and member of the Healthcare and Life Sciences Practice, Dr Ulrica Sehlstedt, Managing Partner and Global Head of the Healthcare and Life Sciences Practice, and Ben van der Schaaf, Partner and member of the Healthcare and Life Sciences Practice, Arthur D. Little

It is a two-way street; established players will be able to tap into a wider pool of talent, access new markets, lower supply chain risks and bring down manufacturing costs. This next transformation in healthcare will therefore likely be beneficial to patients globally.

Insights for the executive

Achieving the benefits of a truly global healthcare ecosystem requires innovation from companies, policy makers and governments in three key areas.

First, accelerate open collaboration and risk sharing across nations and companies. Enable open collaboration between nation states and pharmaceutical companies and other industry players to justify investments. This includes solid legal frameworks, alignment on how IP is treated and action to crack down on counterfeit/black/grey market drugs.

These frameworks should be driven and overseen by global organisations (such as the WHO) to avoid the need for individual pharma companies to align with each nation state.

Establish new risk-sharing models to protect companies from the inevitable challenges that will arise when building new manufacturing capability and supply chains and transferring tech and IP, while ensuring the highest quality levels are maintained. This will lower risks and costs with time as capabilities scale.

Second, facilitate a shift in how technologically advanced companies share knowledge and train local populations to do advanced technical work. This requires collaboration with governments, universities and NGOs to build talent pools and put safeguards in place to protect investment in training and development. Ultimately this will create a larger, more diverse global talent pool.

Third, innovating and operating in new countries and markets will require governments and policy makers to invest in local education and regulations to stimulate the right ecosystem capabilities to drive local R&D, manufacturing and business model innovation. Companies, in turn, can leverage this as they seek to develop new approaches to drug development, market access and distribution in developed markets.

Ultimately, rebalancing global supply chains and bringing innovative medicines and advanced manufacturing capabilities to developing regions will transform global healthcare in five key ways: improving local and global health; improving the economies of developing nations; improving the trust of citizens in their governments and the ability to deliver quality healthcare; derisking the pharmaceutical supply chain and therefore access around the world, providing better resilience globally; and opening new opportunities through access to a wider, more diverse talent pool, innovative manufacturing and distribution approaches, and the ability to effectively target new markets and patient populations.