A groundbreaking discovery led by the University of St Andrews has found a way to turn ordinary household plastic waste into the building block for anti-cancer drugs.

Household PET (polyethylene terephthalate) waste, such as plastic bottles and textiles, can be recycled in two main ways: mechanically or chemically.

Chemical recycling breaks down PET’s long polymer chains into individual units called monomers or into other valuable chemicals.

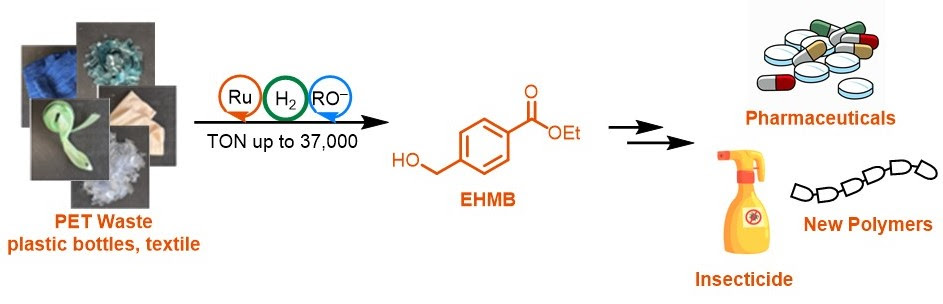

Published in Angewandte Chemie International Edition, researchers discovered that by using a ruthenium-catalysed semi-hydrogenation process, PET waste could be depolymerised into a valuable chemical, ethyl-4-hydroxymethyl benzoate (EHMB).

Remarkably, EHMB serves as a key intermediate for synthesising several important compounds, including the blockbuster anticancer drug Imatinib, Tranexamic acid, the base for medication that helps the blood to clot, as well as the insecticide Fenpyroximate.

Currently, these types of medication are created using fossil-derived feedstock, often using hazardous reagents, producing significant waste.

This groundbreaking research offers substantial environmental benefits compared to conventional industrial methods for producing EHMB, as confirmed by a comparative hot-spot analysis in a streamlined life cycle assessment approach.

This means quickly pinpointing the parts of a product’s life cycle that cause the most environmental impact, so it's known where improvements will matter most.

Additionally, researchers discovered that EHMB can be converted into a new and recyclable polyester.

Lead author of the paper, Dr Amit Kumar from the School of Chemistry at St Andrews, said: "We are excited by this discovery, which reimagines PET waste as a promising new feedstock for generating high-value APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) and agrochemicals."

"Although chemical recycling is a key strategy for building a circular economy, many current technologies lack strong economic feasibility."

"By enabling the upcycling of plastic waste into premium products instead of reproducing the same class of plastics, such processes could meaningfully accelerate the transition to a circular economy.”

The lead of the collaborative partner organisation, TU Delft in the Netherlands, Professor Evgeny Pidko, said: “For catalytic upcycling to become practical, the catalyst must operate efficiently at low loadings and maintain activity during long periods."

"All catalysts eventually deactivate, so understanding when and how this happens is critical to pushing turnover numbers to levels relevant for real applications."

"In this study, we combined detailed kinetic and mechanistic analysis to understand catalyst behaviour under the reaction conditions and used this knowledge to optimise the system towards record turnover numbers of up to 37,000."

"This emphasises the importance of fundamental mechanistic insights to optimise catalyst durability and overall process efficiency."

Dr Benjamin Kuehne and Dr Alexander Dauth from collaborative partner organisation Merck KGaA said: "Pharmaceutical manufacturing generates substantial amounts of waste per kilogram of product."

"There is an urgent need for innovative, sustainable chemical processes and raw materials with reduced environmental footprints."