An inadequate microbial control programme can present a significant risk to patient safety — at the very least product recall — and financial loss to the company. The control of microbiological contamination and root-cause investigations are among the top 10 most observed deficiencies by the US FDA since 2012.

A similar situation exists in Europe based on reports from the MHRA. Annex 1 manufacture of sterile medicinal products The manufacture of both human and veterinary medicines in the EU is governed by EudraLex Vol. 4 Good Manufacturing Practice: “The rules governing medicinal products in the European Union.”

Annex 1 of EU GMP, which specifies guidance for the manufacture of sterile medicinal products, was first issued in 1989, revised in 1996 and updated in 2003 and 2007. With no complete review of the Annex having been done for more than 10 years, a complete review and rewrite was needed.

The Annex needed to catch up with both changes in sterile manufacturing technology (RABS, isolators, rapid microbiological methods) and significant updates in regulatory expectation, the introduction of ICH Q9 for Quality Risk Management, ICH Q10 (which describes pharmaceutical quality systems) and the changes regarding the production of water-for-injection (WFI) to include methods other than distillation.

After a long period of review, discussion and rewrite, Annex 1 has now been released.

It was published in August 2022 with an implementation date of 25 August 2023 — with the exception of the sterilisation of manual lyophilisers, which has an implementation date of August 2024.

The previous 16-page document has been replaced with a 59-page one, each topic has been significantly expanded, new sections have been included and the concept of risk management is embedded throughout.

General summary of changes

There are now 300 different clauses, compared with 100 in the previous version, many of which have been expanded. The new sections include single-use technologies, aseptic operator qualification, application of quality risk, disinfectant qualification for cleanroom surfaces, process water systems (including the manufacture of WFI), other utilities and closed manufacturing systems.

One of the main documentary requirements of the new Annex is the requirement for a holistic contamination control strategy (CCS).

Contamination control strategy

This document, either in one master volume or separate related chapters, will reflect a site-wide strategy to minimise contamination.

Whichever way is chosen, it must be a “living” document, which is kept up to date throughout the lifecycle of the facility. In the published version, there are now approx. 45 times when the Annex states that a particular requirement, measurement or validation should be documented in a site’s CCS.

For established facilities, it probably already exists. Yet, even if the CCS comprises separate documents, manufacturers should try to include links and references — and not rewrite — all their qualification documents.

New facilities should start the CCS as early in the process as possible; it should ideally form part of the design process and be included in URS and DQ documents.

The Annex states: “A contamination control strategy (CCS) should be implemented throughout the facility to define all critical control points and assess the effectiveness of all the controls (design, procedural, technical and organisational) and monitoring measures employed to manage risks to medicinal product quality and safety."

"The combined strategy of the CCS should establish the robust assurance of contamination prevention. The CCS should be actively reviewed and, when appropriate, updated and should drive continuous improvement of the manufacturing and control methods.”

The CCS should describe the control measures and steps to minimise the risk of contamination from microbial, endotoxin/pyrogen and particle contamination. It should include a series of interrelated events and measures that, even if they’re assessed, controlled and monitored individually, their collective effectiveness should be considered together.

The main elements will include the design of plant and process(es), premises and equipment, personnel, utilities, raw material controls, product containers and closures, vendor approval, the management of outsourced activities, process risk management and validation, the validation of sterilisation processes, preventive maintenance, cleaning and disinfection, monitoring systems, prevention mechanisms (trend analysis, investigations, CAPA) and continuous improvement based on information derived from all of the above.

Cleaning and disinfection

The references to cleaning and disinfection within the Annex have been expanded. The word disinfection has been used to replace sanitation as the title of the section. The terminology of “cleaning” has been replaced with “cleaning and disinfection.”

The text notes: “For disinfection to be effective, prior cleaning to remove surface contamination should be performed.” This clarifies current best practice that cleaning and disinfection are two distinct activities trying to achieve different things.

Cleaning is defined as “a process to remove contamination, such as product or disinfectant residues.” Disinfection is subsequently defined as “the process by which the reduction of the number of micro-organisms is achieved by the irreversible action of a product on their structure or metabolism to a level deemed to be appropriate for a defined purpose.”

Residues

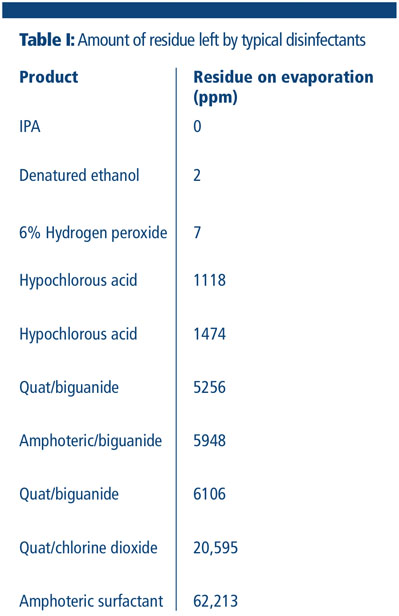

Many common and well used disinfectants, such as amines, amphoterics and quaternary ammonium compounds, leave significant residues on a surface, which can subsequently have a detrimental effect on the effectiveness of the disinfectant used (Table I).

This is acknowledged in the new Annex: “Cleaning programmes should effectively remove disinfectant residues.” Pharmaceutical companies have been cited for the presence of (visible) residues, which has often been seen in the past as an indication that a cleaning and disinfection process is not fully in control.

There are currently no approved or published methods to assess the amount of residue on non-product contact surfaces, so most facilities conduct a visual test.

Alcohols and hydrogen peroxide are the only two disinfectants that truly leave no residue. All other disinfectants leave a residue; some are worse than others, some are easier to remove than others. Some disinfectants claim that they are “no” or “low” residue, but there is no accepted definition of low residue.

Even if a disinfectant is “low residue,” is that actually a relevant measure if it’s difficult to remove? It must also be remembered that all detergents leave a residue. So, disinfectants either need

- to be wiped to dry after the contact time

- have an immediate residue removal stage added with water or alcohol

- include a routine clean with a detergent to remove residues at a validated point.

Rotation

Regulatory guidelines are not aligned on the subject of disinfectant rotation and the number of disinfectants that need to be used. EU GMP Annex 1 previously stated that “more than one type of disinfecting agent should be employed,” and this is repeated in the new revision.

Additionally, it states why, to ensure that when they have different modes of action, their combined usage is effective against bacteria and fungi. In line with other regulatory guidance, it also clearly states that disinfection should include the periodic use of a sporicide.

This leads to many questions from end users. How many disinfectants do I need? Must I rotate disinfectants with different modes of action? Is this because of resistance? What does periodic use mean? This all becomes easier to answer when we remember that risk management is embedded in the philosophy of the Annex.

So, the number and frequency of disinfectants to use will depend on the specific environmental monitoring (EM) programme and periodic auditing of the cleaning and disinfection process.

Our discussions with the MHRA confirmed that if EM results/trends are under control, there would be no stipulated need to have achieved this using a rotational disinfectant programme or disinfectants with different modes of action.

Many facilities will routinely use a broad-spectrum disinfectant in rotation with a sporicide that’s kept for intermittent or action point use. This is mainly because of the corrosive or aggressive nature of many sporicidal biocides rather than any concerns about resistance.

The more recent availability of highly effective cleanroom sporicides with no classified hazards may change this approach. A typical biodecontamination programme would consist of daily disinfection with a broad-spectrum disinfectant or alcohol and/or periodic use of a sporicide based on EM.

Every day after cleaning and disinfection (unless using alcohol or hydrogen peroxide), rinse with WFI or alcohol or wipe to dry. After spills, for maintenance or periodically to remove built-up residues, a clean should be done with a neutral, low foaming detergent.

Disinfectant qualification and validation

There is increased emphasis on disinfectant validation; the process, not just the disinfectant, needs to be validated. Validation will need to relate to the manner in which the disinfectant is used — whether by spraying, wiping, fogging, etc. — and on the surface on which it will be used.

It will not be sufficient to just do standard suspension testing of the disinfectant. The new Annex is very specific: “Demonstrate the suitability and effectiveness of disinfectants in the specific manner in which they are used and on the type of surface material or representative material if justified.”

High risk surfaces will need to be identified and documented in the CCS. Annex 1 also states that the validation work done “should support the in-use expiry periods of prepared solutions.” This will not only be relevant for dilutions made from concentrate, but also for ready-to-use (RTU) trigger sprays and presaturated wipes.

Efficacy testing will be required for both the unopened product at the end of its shelf-life and also during its in-use period. EM should be done to assess the effectiveness of the disinfectant programme and be suitable to detect any changes in the type of house isolates identified.

For instance, the microbial flora in a facility can change as a result of external factors (such as local building work, seasonal variations and personnel changes). Annex 1 now clarifies that: “Micro-organisms detected in the Grade A and B areas should be identified to species level.

Consideration should also be given to the identification of micro-organisms detected in Grade C and D areas.” Like the previous version, Annex 1 gives clear guidance about the use of disinfectants and detergents.

“When the disinfectants and detergents are diluted/prepared by the sterile product manufacturer, this should be done in a manner to prevent contamination and they should be monitored for microbial contamination.”

This is repeated in the updated Annex 1, but the exception for sterile dilutions is removed. “Dilutions should be kept in previously cleaned containers (and sterilised when applicable) and should only be stored for the defined periods.”

However, it acknowledges that many disinfectants are now purchased ready-to-use from a manufacturer and these don’t need to be qualified if provided with a COA or COC from a qualified vendor. It continues to state: “Disinfectants and detergents used in Grade A and grade B areas should be sterile prior to use.”

It additionally requests that consideration should be given to disinfectants used in Grade C and D areas also being sterile prior to use; this would be decided via risk assessment and documented in the CCS.

In summary

There is more emphasis on separate cleaning and disinfection steps, which reflects current best practice. The periodic use of a sporicide is specified, which brings the guidance into line with other regulatory documents.

The removal of disinfectant residues is mentioned more than once, so consideration needs to be given to “no residue” disinfectants or disinfectants with easily removable residues. “Low residue” disinfectant has no definition.

Disinfectant products need to be validated as being efficacious for the duration of use, but data from a qualified vendor can be used. Disinfectant efficacy needs to be proven on specific facility equipment, surfaces and associated processes. All decisions need to be made based on quality risk management and EM trends, and captured within the facility’s CCS.