There has been considerable discussion about the concept of patient centricity in the pharmaceutical community, with attention being recalibrated on the ultimate goal — making it easier for the patient to reach improved health outcomes. This perspective is underpinned by the recognition that what is best for the patient will lead to beneficial outcomes for all stakeholders, including the drug company, the healthcare provider and the supporting community of associated service providers.

There is a famous quote from former United States Surgeon General, C. Everett Koop: “Drugs don’t work in people who don’t take them.” It is estimated that less than one third of all prescriptions written are actually filled at the pharmacy by patients. Wide-ranging studies have shown medication adherence rates for life-threatening diseases — including diabetes, heart disease and oncology — can be as low as 30–40%. With the benefit of interventional techniques and developing technologies, adherence rates have been shown to improve; however, these programmes are not broadly adopted within industry at scale and have neither significantly reduced the overall cost of healthcare nor benefitted large populations.

Patients may be non-adherent for a variety of reasons, some conscious and some unconscious. Certainly, we are all admittedly forgetful when it comes to taking our medicine on time or being diligent about timely refills of those prescriptions. Cost can also be a significant factor whereby patients will consciously stretch their medication supply or simply go off therapy. In either instance, doing so will hamper the health impact of their prescribed therapy or worse; taking a drug holiday while prescribed an anticoagulant could potentially put their life in jeopardy.

Other considerations may be unwanted side-effects or a lack of understanding about how to optimally take the medication, such as taking with food or alternatively avoiding food for some period of time, resulting in reduced effectiveness. Fear or general lack of understanding can also inhibit the path to improved health by affecting the patient’s perception of the medication and their willingness to be compliant.

Likewise, the patient may not physically experience the benefit of the drug and, in some instances, may have a negative perception owing to the unwanted side-effects. Hypertension is the classic example; the patient may have high blood pressure but generally not feel the effects of their disease. However, they may experience considerably unpleasant side-effects as a result of their course of treatment.

Likewise, a similar scenario plays out in popular cholesterol lowering medications. By scale, these two examples are noteworthy; in the US, with a population of more than 300 million people, of which 75% are adults, it is estimated that one in every three adults has hypertension, whereas 10–20% of adults have high cholesterol. A large-scale patient-centric approach to benefit medication adherence would have significant positive health and economic impacts.

Focusing patient centricity in clinical trials

In addition to challenges with patient adherence to medication in clinical trials, sponsors and study organisers are also constantly faced with hurdles such as patient recruitment and patient retention. As the industry is tasked with further expediting drug development and decreasing clinical study duration, FDA is increasingly requiring additional studies and further data to prove long-term safety and comparative effectiveness, including post-marketing studies once the drug is commercially available in the market.

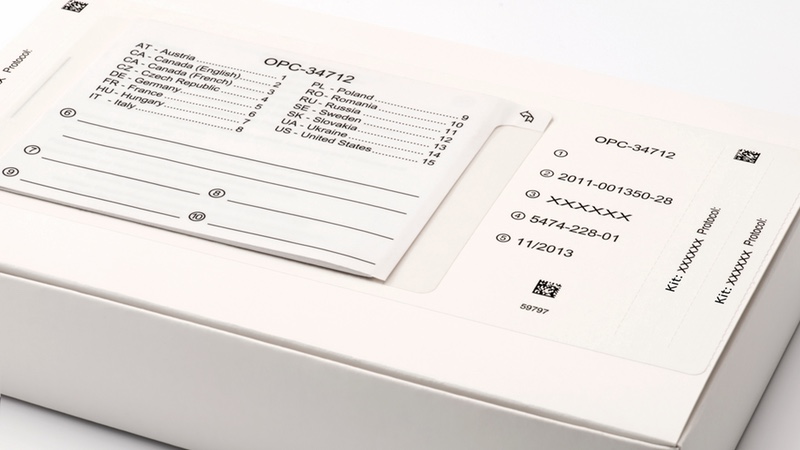

This trend is coupled with an increasing percentage of drugs being brought to market for very specialised disease states and narrow therapeutic indications. This wave of specialised medicines and the ongoing need for treatment-naïve candidates, paired with cost pressures in the R&D sector, has increased the use of multinational studies. These complex studies in turn create the requirement for multilingual labelling. This can result in the creation of investigational medicinal product (IMP) study materials that may contain upwards of 16–20 languages on a single label.

Clinical trial professionals are left to balance all of these demands and creatively identify initiatives to keep the focus on the patient. At a surface level, these competing priorities may seem to be in direct conflict. However, when one looks at the situation from a broader perspective, the focus on patient centricity clearly generates tangible value and outweighs the short-term inefficiencies created by opting for a solution solely based on speed or cost.

Patient centricity in package design

A practical example of patient centricity in action can be found in package selection for investigational studies. When looking to initiate a clinical study, a sponsor company may be evaluating whether to choose a bottle or a unit dose blister in a calendarised format for their clinical study material.

Looking simply at the short-term criteria of expediting material for study initiation, when a difference of weeks or days can be considerable, the path of selecting a bottle would be a logical solution. It is a cost-effective packaging option, it is relatively “off the shelf” in its availability, it can be hand filled by a clinical packager with minimal start-up costs, has an acceptable stability profile for barrier properties and is child resistant.

With the increased use of multinational studies, investigational medicinal product (IMP) materials may contain upwards of 16–20 languages on a single label

Conversely, when evaluating the development of a unit dose adherence package, the company might find that it may involve a longer lead time for development and be more costly to produce. Looking from a short-term perspective and the immediate pressures of cost and expediting, the choice leaves little room for debate. However, if the sponsor company is taking a holistic approach with a focus on patient centricity, the broader economics absolutely point to the use of a patient-centric package.

Using a calendarised unit dose blister format or compliance/adherence packaging enables sponsor companies to both address the needs of the patient as well as positively impact the desire for better data, more efficient studies and lower total delivered cost. The use of this style of package allows patients to take medication exactly as prescribed and track their usage, rather than a bulk approach in a bottle format. Physicians can capture vital information on the package, including the specific date to start the therapy and any other pertinent notes for the patient. With the returned package, the patient can physically demonstrate to clinical providers that they have taken the product as prescribed. Furthermore, technologies are available that can provide real-time tracking of patient dosing, allowing for clinical interventions to ensure proper adherence while the study is in progress.

These technologies and principles extend to other delivery forms such as injectables. The ability to prompt, monitor and even track real-time information is a powerful tool. Likewise, with the advent of Bluetooth and nearfield communication technologies, packages with integrated technology can capture real-time information about side-effects or other vital information as patients take the medication during the course of treatment. Better adherence leads to healthier patients and more valuable study data.

Poor adherence can be rectified and corrected as it happens. Better information gathering can lead to improved patient retention, a significant cost in clinical trial administration and a persistent challenge in study duration. It is estimated that, in the industry, clinical studies on average have a 30% drop out rate. With more adherent investigational study patients, health outcomes are improved and better retention is realised, translating into reduced total delivered cost, more valuable data generated and studies executed more efficiently.

Patient centricity in clinical supply chain logistics

Another focus point for realising patient centricity in clinical trials is in the area of study design and administration. Considerable interest is being focused on Direct-to-Patient models, in which patients may minimise or in some instances avoid the need to come to a hospital or clinic to receive the study drug, as well as provide critical health feedback. In this scenario, patients are engaged by clinical trial or healthcare professionals in a home setting and the study drug is physically delivered to their home by a trained specialist. Clearly, this model is not applicable for all studies and disease states, but for certain programmes there can be considerable benefit to the patient and the study.

In certain geographies, patients in a traditional clinical study may have to travel significant distances to participate, which can considerably hamper patient recruitment and retention. In a Direct-to-Patient model, the study effectively comes to them. This model may increase the cost of study administration for the sponsor company; however, by executing the study in a more patient-focused approach, the sponsor company can realise significant benefit through patient recruitment and retention, again translating into better data, more efficient studies and a faster path to completion.

Patient centricity in a global world

One of the increasing challenges in taking a patient-centric approach to clinical study execution is the growth in multinational study execution. Often, supplies are designed to pool, so that multiple languages are provided and materials can be directed to individual countries as needed.

This scenario forces sponsor companies to either manage a multitude of language-specific supplies or focus on common supplies — whereby they condense information owing to the shear amount of text being added, often squeezed into a multi-page booklet.

Careful consideration must be paid to graphics that are common to all languages and cultures to ensure patients can clearly comprehend considerably distilled opening instructions, dosing regimens and other key information. Rather than a traditional pooled supply approach, some companies have developed newer strategies for just-in-time (JIT) labelling or late stage customisation logistics, whereby they label study materials according to country specific requirements at the time of drug dispatch.

This can reduce the complexity of a scenario in which they would be trying to accommodate 16 different languages on the same label in a multi-page booklet approach. This JIT strategy might decentralise supplies but may bring other benefits, such as meeting the language and cultural needs of patients in their geography, as well as those of the study administration.

Patient focus yields powerful results

The industry is only in the infancy of its journey towards patient centricity; but, it is clear that with a focus on the patient, many tangible benefits can be realised by drug companies in the development and commercialisation of life-saving medicines.

With so many significant breakthroughs during the past decade, it is exciting to see where this patient focused journey will lead as new patient breakthroughs are happening every day.